Sea blog

Walther Herwig III, 443rd cruise

Hermann Neumann and the team

Duration: January 25/26 to February 26, 2021

Area: North Sea

Purpose: International Bottom Trawl Survey (IBTS), 1. Quarter

Cruise leader: Hermann Neumann, Thünen-Institute of Sea Fisheries

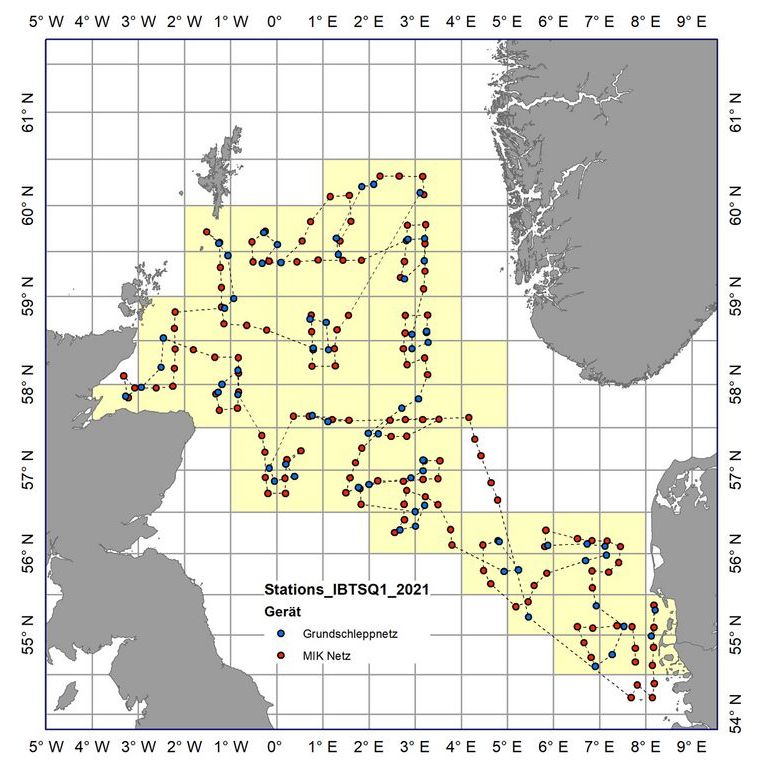

The International Bottom Trawl Survey (IBTS) is an internationally coordinated programme of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES). The survey aims to provide ICES assessment and science groups with a time series of consistent and standardized data for examining spatial and temporal changes in (a) the distribution and relative abundance of fish and fish assemblages; and (b) of the biological parameters of commercial fish species for stock assessment purposes.

The main objectives are to determine the distribution and relative abundance of pre-recruits of the main commercial species with a view of deriving recruitment indices. This means that the number of juvenile fish caught from one species can give insight on how many individuals of this species are to expect in the season to come. This data is used to provide managers with advice for setting the TAC, the total allowable catches of commercial species. Importantly, we monitor the changes in the stocks of commercial fish species independently of commercial fisheries data.

At night we work with plankton nets to determine the abundance and distribution of late herring larvae, which is used as a recruitment index in North Sea herring.

Additionally, we collect hydrographical and environmental information at every station.

Our research vessel is undertaking research on a 24/7 basis.

Finally the time has come - after a domestic quarantine and negative Covid19 test, we are allowed on board the Walther Herwig. Corona has many implications: There is a special hygiene concept, masks are compulsory, and the intermediate port of Kirkwall on the Orkney Islands has also been cancelled for safety's sake. This means we will spend 31 days without interruption on the wintry North Sea.

We, that is seven colleagues from the Thünen Institute of Sea Fisheries, four student assistants and of course the 24-strong ship's crew. Together with other ships, we want to study the most important commercial fish species in the North Sea in order to make statements about the current stock development.

While we are still setting up the labs, it's "Cast off!" and we move away from the pier on Herwigstraße. The maritime city shows itself from its most beautiful side: bright sunshine and blue skies bid us farewell. Almost like a diamond, the silver anodised aluminium façade of our institute sparkles and slowly disappears on the horizon. After passing the lock, we steam to the first stations in the North Sea.

We are excited to see what awaits us on this journey.

Greetings from on board

Sakis Kroupis

"Heave up in 10 minutes," resounds through the loudspeakers of the Walther Herwig. Late on Sunday afternoon, the net is hauled in just in time before sunset.

This is important because, according to the specifications in the IBTS programme, fishing should only take place during the day so that all results remain comparable over the years. Fish behave differently in the dark than during the day; some species move further away from the seabed under cover of darkness. This means that day and night catches cannot be directly compared.

When the haul - as the catch is called in fishing - is on deck or in the laboratory, we immediately start sorting. Survivable fish species such as sharks and rays are placed directly into small holding tanks and gently released back into the sea after data collection.

After sorting, the number, weight, sex, maturity and length of each fish species are determined. In some cases, ear stones (otoliths) are taken so that the exact age can be determined later in the laboratory on land. These data are important for estimating the population of commercial species. Only if we know the sex ratio, the proportion of sexually mature animals and also the age and length composition, can we make reasonably reliable predictions for stock management.

Especially sexing and maturity determination requires a lot of experience and cannot be learned overnight. That is why it is important that every trip is accompanied by experienced colleagues. We are still lucky with the weather.

Compared to the trips of the last few years, there is relatively little wind. So all the colleagues and our student assistants have been able to settle in well and go through a perfect familiarisation phase. In winter, the North Sea can be very uncomfortable, even for experienced seafarers. Heavy storms can interrupt our work for several days.

As soon as the trawling is over with the sunset, the night shift starts working. After all, no valuable ship time should go unused.

Right after the last haul, the MIK net is prepared. The MIK is a very large plankton net for catching large herring larvae (20 - 30 mm long). As these larvae are very agile and can swim quickly, the net must be particularly large. We use it in the dark, because during the day the larvae would notice the net too early and avoid it. The MIK has a ring-shaped inlet 2 metres in diameter and is over 13 metres long.

The data obtained indicate the distribution and quantity of surviving larvae of the North Sea herring stock and provide information about its offspring strength.

Since almost the entire ship's crew is deployed during daytime fishing, the "science" crew has to help out on deck during the night to drive the plankton net. The net is towed horizontally at 3 knots, slowly lowered to a maximum water depth of 100 metres, or at least 5 metres above the seabed, and brought up again.

Together with the watchkeeper, the officer on duty and an experienced sailor, the MIK net is set out in almost any weather. Only when the wind force is clearly above 15 m/s (7 Bft ) do we carefully consider whether it is still safe to set the net. If the net is caught by a strong gust of wind when it is being hauled in, it can be dangerous. You then have to act very carefully and coordinate well with your colleagues on deck. The experience and prudence of the seamen involved helps us a lot. But this is the only place where we find them, the herring larvae!

Still in the on-board laboratory, the plankton samples are sorted for fish larvae and the herring larvae are identified, measured and the data entered. They are later evaluated together with the data of the other survey participants and reported to ICES.

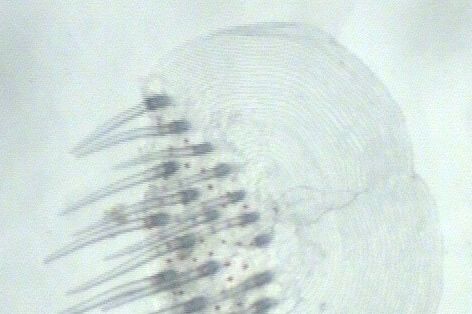

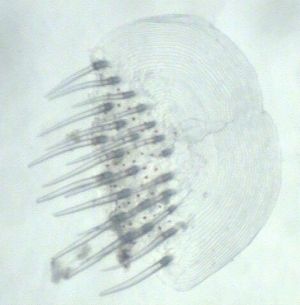

In recent years, more and more sardine larvae have been found. They look very similar to herring larvae. It takes experience and knowledge to safely separate the two species. An important feature is the position of the ventral fin in relation to the transition between stomach and intestine. In the sardine it sits directly below, in the herring clearly behind. In the case of young larvae that have not yet developed a ventral fin, all the muscle segments between the neck and the anus must be counted. Herring larvae always have more of them than sardine larvae.

Finally we have reached the exciting and species-rich stations in the north. While you catch around 15 species of fish in the southern North Sea, there are more than twice as many in the north. Large pollack, cod and haddock are a real highlight, especially for the first-timers among us. But even for the "old hands" there is always a surprise here in the north. On our very first haul, we caught something special: the boar fish (Capros aper).

The boar fish is actually well known to us from trips to the north-east Atlantic to the west of Great Britain, where it is usually found in large shoals. In addition to their vivid red colouring, boar fish have characteristics that do not make them particularly popular with fishermen: they have strong, thorn-like fin rays and scales covered with fine bristles. If you catch large numbers of boar fish in the net, they get caught in each other because of the many bristles and thorns, and you can hardly get them out of the net. In addition, their fin rays bite into the target species caught in the fishery, which often makes the catch worthless.

For a long time, boar fish were considered commercially unviable. They are too small for direct human consumption, although they have quite tasty meat. For a long time, it was also not possible to produce fishmeal from them. None of the fishmeal mills could cope with their strongly armed bodies. It was only after the mills were adapted to these small, strong fish that it was possible to produce a relatively high-quality fishmeal from them. After the stock grew strongly in the early 2010s, a targeted fishery for the boar fish quickly developed.

However, to find boar fish here in the North Sea near Norway is not an everyday occurrence for us. The fact that we caught it together with the bluegill (Helicolenus dactylopterus), a relative of the redfish, which also does not occur regularly, indicates a strong influx from the north-east Atlantic, which is not unusual this far north. Every now and then, such "exotics" from the Atlantic reach the North Sea and can get into our nets.

Seafaring romance in an industrial area. Far from home, we gaze daily at the seemingly endless blue of the sea; around us, only untouched nature. This is how many imagine a journey across the North Sea. But the reality is different. There are hardly any days when we are really alone. There are almost always ships, wind farms or oil platforms on the horizon.

And it's not only this sight that makes us think, but also the things that end up in our nets besides fish.

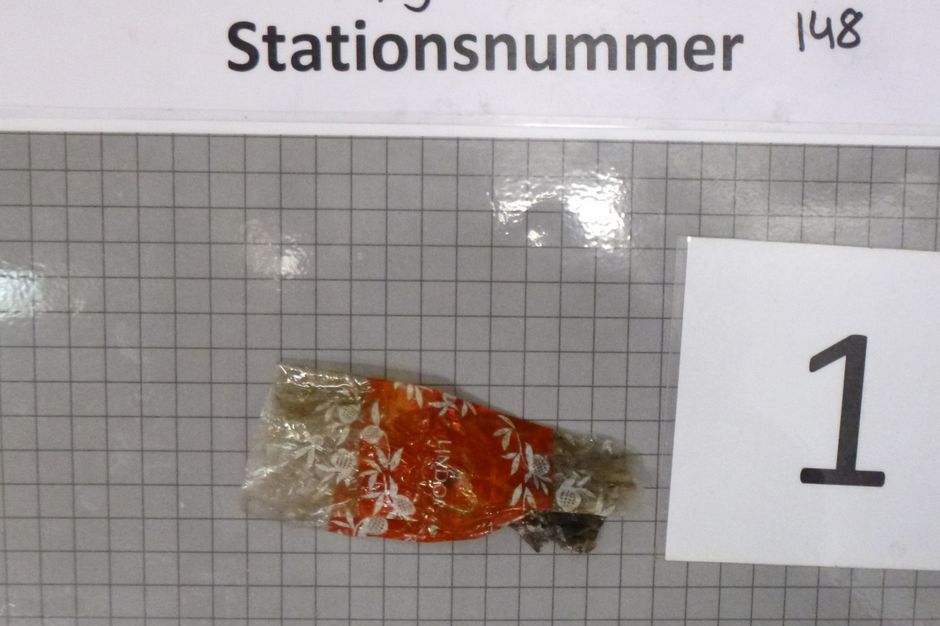

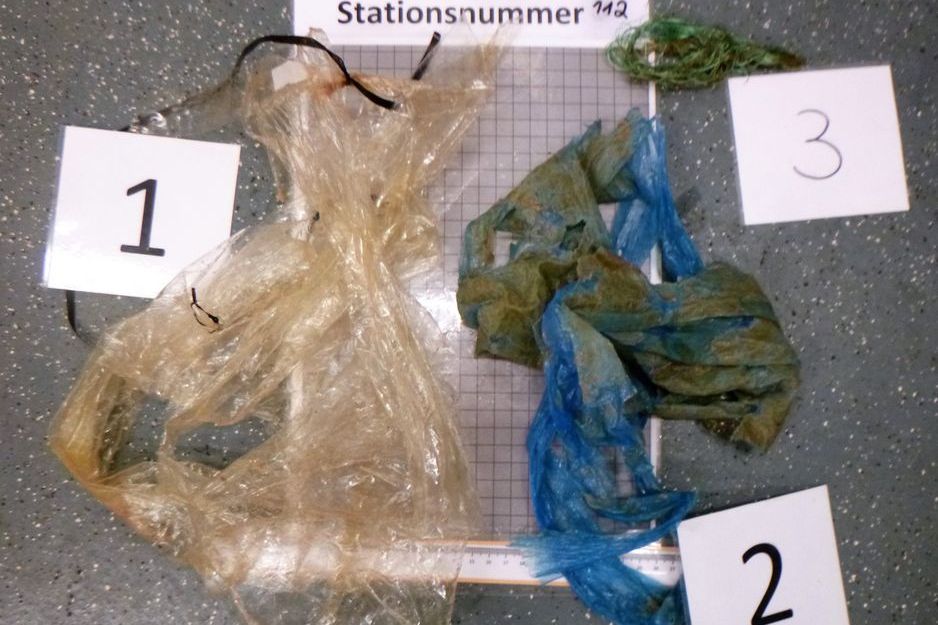

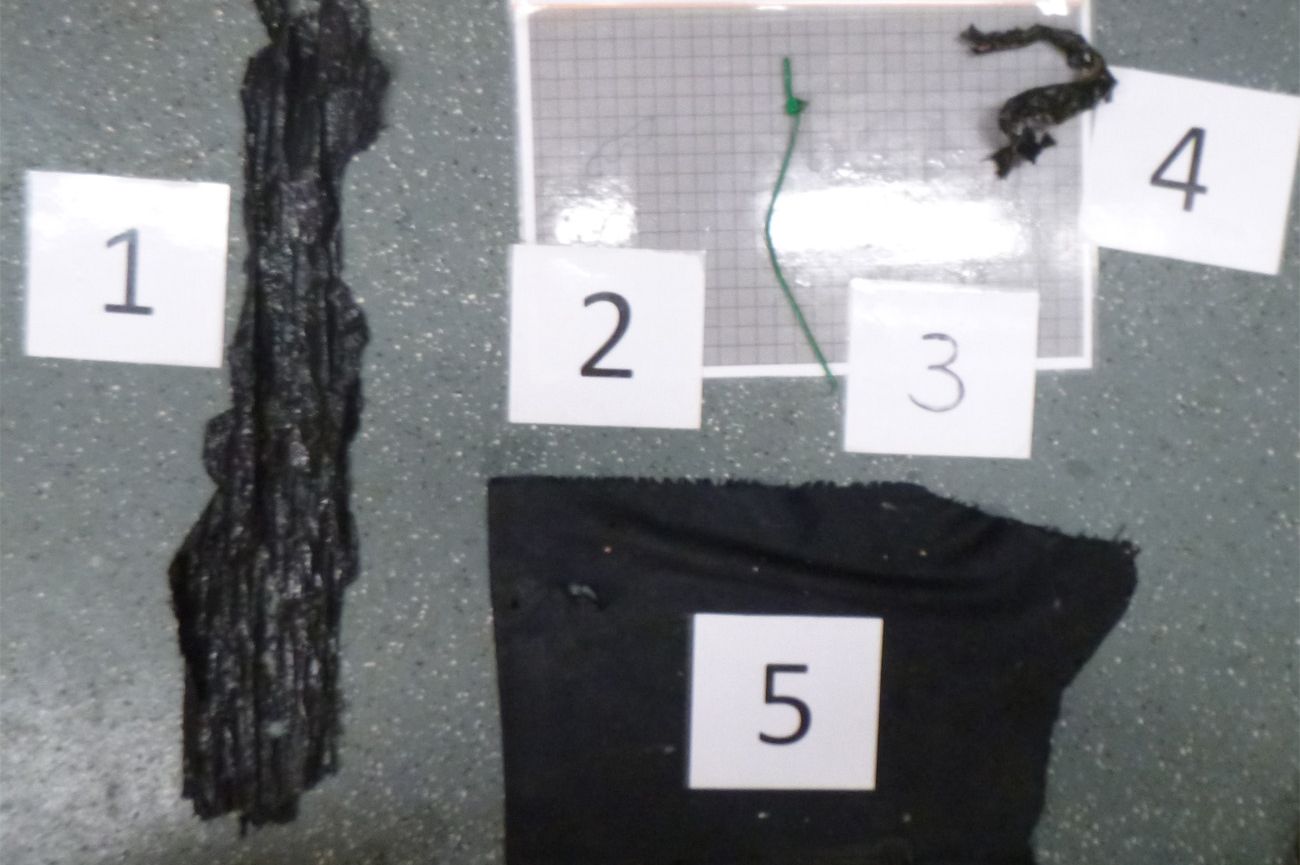

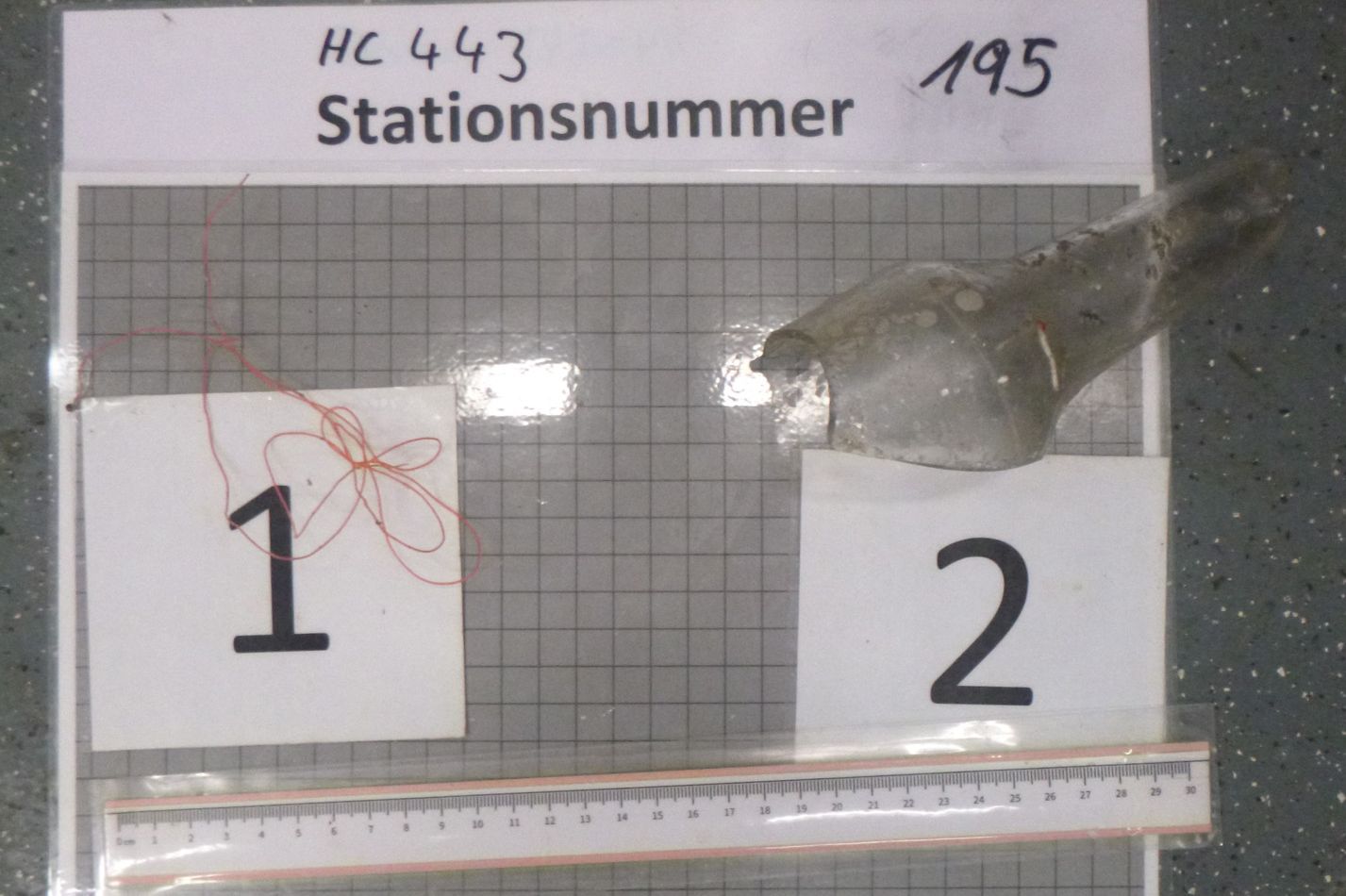

While fish species are sometimes more or less present, one thing is almost regularly found on our stations: Marine litter. Rubbish that has gone overboard intentionally or unintentionally, that has found its way into the sea via detours from inland or that has been lost during fishing.

Together with the ships of the six other nations with which we are conducting this survey, we cover the entire North Sea when sampling. This good coverage is not only suitable for an inventory of fish stocks, but also for an inventory of human remains in the sea. That's why we also document the rubbish according to a detailed protocol. So far, we have made 42 fisheries hauls covering large parts of the southeastern and northern North Sea. In 36 of the 42 hauls we were able to document litter - a rate of 86%.

In our net catches we find almost everything that can also be found on land in rubbish dumps: Beverage cans, car tyres, metal parts, bottles, packaging, cigarette butts, etc. The main component of the rubbish is plastic. This poorly degradable material is found in our nets in the form of fishing lines, foil and food packaging. Plastic is known to break down into smaller and smaller microplastic fragments, but never to be completely degraded. These small plastic fragments are too small to be caught by our nets, so we can only guess at the actual amount of waste on the seabed. But they are ingested by marine organisms and can return to us through the fish we consume.

Our hauls are a clear reminder of the pollution of ecosystems and once again demonstrate how important it is to pay attention to clean seas - even if they still shine in a natural, deep blue when viewed from above and pollution is therefore often forgotten.

Even with our smallest fishing gear on board, the MIKey-M net, we catch exciting creatures. The ring-shaped opening of the MIKey-M net has a diameter of only 20 cm and sits on the large plankton fishing gear (MIK). The special feature is the small mesh size of only 300 µm (about 1/3 mm). We use it to catch tiny organisms in the plankton such as fish eggs, small fish larvae and crustaceans, but also interesting larvae of other sea creatures, e.g. starfish.

Many people think of starfish as sea creatures that only inhabit the bottom. But it is a special and mysterious way to get there: In most starfish, the male and female gametes are first fertilised outside the body in free seawater. And even after that, the nascent starfish does not immediately continue on the bottom. It first drifts around freely in the water for weeks as a larva. Two conspicuous larval forms can be distinguished: First, the Bipinnaria larva, which is not five-armed like an adult starfish, but bilaterally symmetrical. In most species, this larval form transforms into the Brachiolaria larva, which has an adhesive disc, attaches itself to the seabed and finally transforms into the juvenile starfish.

On our trip we caught hundreds of larvae of the starfish Luidia sarsi with the MIK. This species has two surprises in its development: it simply skips the last larval form, the Brachiolaria, and transforms directly from a very large and pretty Bipinnaria larva into the finished starfish. Moreover, the larva lives much longer than others in the plankton (over a year). With this tactic, the species can colonise habitats further away from its place of origin.

At the moment we have "bad weather" and we are slowly trudging against high seas to the next MIK station. The ship rocks a lot, it's uncomfortable and there's not much chance of sleep. But whenever you get to see such extraordinary things when you look through the binoculars, you know why you put yourself through all this trouble.

After about three weeks, our journey is coming to an end. At home, the onset of winter brings plenty of snow, but we don't notice much of it here. On the contrary: the unusually good sea weather for this time of year has made it possible to do our work without any downtime. And even when the weather was a little rougher overall, we were still able to move to quieter areas where we could work in peace. Now the last data is being entered, the labs scrubbed and all the equipment packed and prepared for departure. Once again, bustling activity on board before land life has us firmly in its grip again.

For technical reasons, it was decided to take the ship directly to Wilhelmshaven for the scheduled shipyard time. After the Walther Herwig made its way through the ice in the harbour basin, it now lies well moored at the pier in Wilhelmshaven. Since the ship is not moored directly at the institute in Bremerhaven as usual, we have to master some logistical challenges once again. Due to the Corona pandemic, it is currently only possible to move a large number of people from A to B at once with great precautions. But in the end, even that will be overcome.

We have now been at sea for a good three weeks and were ultimately able to complete the programme successfully. We "steamed" a total of around 3,650 nautical miles in order to sail our planned 67 fishing hauls and 144 plankton nets - ten more than required.

There was also largely good news from the colleagues of the research vessels of other countries involved in the "International Bottom Trawl Survey", although some had to deal with bad weather more than we did. So overall, the international "winter inventory" of fish stocks was a success. But much of the work still lies ahead. Especially the analysis of the age structure of the fish stocks based on the ear stones (otoliths) will take some time. For cod, haddock and whiting alone, more than 2350 such otoliths were taken, which now have to be read in the domestic laboratory. Similar quantities of otoliths are also to be analysed from other species, such as herring, sprat, sardine, anchovy, mackerel and plaice.

The data from the fishery hauls and the herring larvae from the plankton catches are to be uploaded to the databases of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) between mid and late March, where they will be available to the public. Over the course of the next few months, these data will be reviewed by scientists from all participating nations. Only then, when the landing data from the fisheries are also available and analysed, will we be able to make reliable statements about the state of the fish stocks.

This is where this sea blog ends. Until then and best regards

Sakis Kroupis and the "Team Herwig"